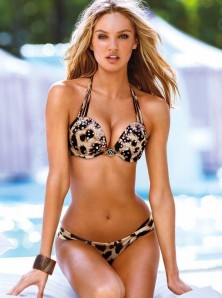

Every December, she falls from heaven to graces us with her presence. She must be an Angel of some sort, but how did she transform from an androgynous, fully clothed, golden humanoid into a sexy, unabashed, barely clothed golden goddess? Her beautiful, bronzed and toned body prance atop the catwalk as you sit down your bag of peanut M&Ms. You know the next two hours will be a huge blow to your psyche, but it’s too late; you’re already hooked. Even in today’s fast-food, overindulging, carbohydrate-addicted world, she’s able to maintain a hot figure that has you sitting on your couch envious. As her unthinkably long legs, thin waist and surprisingly large breast strut down the runway, you stare in awe thinking, “why can’t I look like that?” She’s wearing nothing more than a bra, underwear, and plethora of self-confidence, there’s no way she could possibly have anything more to hide. What’s her secret?

She’s teaching you what the female anatomy should look like. She’s selling you the body you want, along with a flood of insecurities and disappointment. She’s encouraging girls to sexualize themselves at younger and younger ages. No, a pushup bra is not Victoria’s Secret, but she won’t tell you that. First, let’s explore the evolution  of Victoria’s Secret, from a boutique the founder Roy Raymond sought to provide men a place to buy lingerie for their wives without feeling like a pervert, to the company that is less about the product and more about the models, or Angels, that mascot sexiness. Then, we’ll explore Victoria’s Secret imperative, overzealous airbrushed advertising that define sexy from a deontological ethical perspective. Maybe then we can distinguish if these sultry Angels are role models teaching us to love our bodies or misleading us to confuse airbrushed lingerie cover models with role models.

of Victoria’s Secret, from a boutique the founder Roy Raymond sought to provide men a place to buy lingerie for their wives without feeling like a pervert, to the company that is less about the product and more about the models, or Angels, that mascot sexiness. Then, we’ll explore Victoria’s Secret imperative, overzealous airbrushed advertising that define sexy from a deontological ethical perspective. Maybe then we can distinguish if these sultry Angels are role models teaching us to love our bodies or misleading us to confuse airbrushed lingerie cover models with role models.

Her story from the Red Light District to the Catwalk

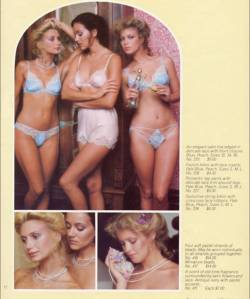

Stanford Graduate School of Business alumnus Roy Raymond founded Victoria’s Secret in 1977 in San Francisco, California. After feeling embarrassed and treated like an unwelcomed intruder whenever he purchased lingerie for his wife at department stores, Raymond sought to establish a store in which men could feel comfortable buying lingerie. During the 1970’s and 1980’s, the underwear business had a great divide. The majority of American women bought pragmatic Fruit of the Loom, Hanes or Jockey underwear in packs of three at mass retailers. Racks of ugly floral-print nylon nightgowns complimented the dull and frumpy lingerie department stores had to offer. Fancier items were available, but usually only purchased for special occasions, like honeymoons. The lacy thongs and padded push-up bras normative in every girl’s underwear drawer today were niche products found “alongside feather boas and provocative pirate costumes at Frederick’s of Hollywood,” (Adler, Newsweek).

After grossing more than $500,000 in its first year of business, Raymond sought to expand Victoria’s Secret from a headquarters and warehouses to four new store locations and a mail-order operation (Pimental, San Francisco Chronicle). While Victoria’s Secret sales grew, so did its niche within the underwear market as a burlesque lingerie boutique. The first catalogs Victoria’s Secret sent to customers were inspired by Victorian boudoirs slightly resembling a brothel, featured lonely women in nightgowns and garter belts. By 1982, Victoria’s Secret sent out their 12th catalog, with catalog sales accounting for 55% of the company’s $7 million annual sales (Schiro, NYT). Raymond’s philosophy for starting Victoria’s Secret, to focus on selling lingerie to male customers, became increasingly unprofitable and led Victoria’s Secret into bankruptcy. This ultimately forced Raymond to sell Victoria’s Secret to Lesie Wexler of Limited Stores Inc. in 1982, the event that ultimately shaped the company we know today. Wexler rein over the company lifted lingerie out of the red-light district, launched it onto the runway and into the underwear drawers of mainstream America.

In 1986, Victoria’s Secret was the only national chain of lingerie stores, with one of the fastest growing mail-order business and best selling catalogs in the clothing industry. As the company moved its headquarters to Columbus, Ohio, The Limited infused Victoria’s Secret with its retail expertise. Victoria’s Secret boosted their

selection to large assortments with colors and fabrics related to the fashion industry. By focusing their attention to fit, Victoria’s Secret began to focus more on the female customer and created the customer loyalty that propelled them into success. Within five years after the purchase, The Limited transformed the lingerie boutique into a 400-store retailer, stealing the underwear market share from department stores (Groves, LA Times). By making sexy lingerie affordable, accessible and acceptable, Victoria’s Secret created a middle ground for intimate apparel. In expanding, Victoria’s Secret aimed to use unabashed sexy high-fashion photography in their advertisements to sell middle-priced underwear, much like the company does today (Adler, Newsweek). The company’s introduction of sexy advertising to help transition their name in mainstream America provided the platform for the sexual advertising the company is known for today.

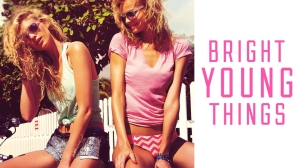

Let’s fast-forward to the Victoria’s Secret of today. Victoria’s Secret’s over 1,000 stores across the US hold one third of all purchases in the intimate apparel industry (Barbaro, NYT). Along with its release of CDs featuring the prestigious London Symphony Orchestra playing romantic classical music, swimwear and beauty lines launched at the turn of the millennia, Victoria Secret launch of Pink in 2002. As a lingerie line targeted to 15 to 22 year olds, the launch of the line aimed to introduce teenagers to Victoria’s Secret  stores. This was a game changer. Victoria’s Secret may claim Pink is for college women, but their Chief Financial Officer Stuart Burgdoerfer made it clear Victoria’s Secret was trying to tap into a teen audience when asked about Pink, stating “when somebody’s 15 or 16 years old, what do they want to be? They want to be older, and they want to be cool like the girls in college, and that’s part of the magic of what we do at Pink,” (Wattenburg, Washington Times). But why is this problematic? Accusations of sexualizing teens is the topic of numerous change.org petitions sparked by concerned mothers’, especially concerning the Bright Young Things Spring Break collection. Pink features underwear in this collection with an array phrases reading, “Call Me”, “Wild”, and “Feeling Lucky?”, to name a few (Change.org).

stores. This was a game changer. Victoria’s Secret may claim Pink is for college women, but their Chief Financial Officer Stuart Burgdoerfer made it clear Victoria’s Secret was trying to tap into a teen audience when asked about Pink, stating “when somebody’s 15 or 16 years old, what do they want to be? They want to be older, and they want to be cool like the girls in college, and that’s part of the magic of what we do at Pink,” (Wattenburg, Washington Times). But why is this problematic? Accusations of sexualizing teens is the topic of numerous change.org petitions sparked by concerned mothers’, especially concerning the Bright Young Things Spring Break collection. Pink features underwear in this collection with an array phrases reading, “Call Me”, “Wild”, and “Feeling Lucky?”, to name a few (Change.org).

Let’s not forget about the notoriously glamorous Victoria’s Secret Annual Fashion Show. Once known best for their catalogs sporting everything from playful to practical lingerie featured on sexy models peering from the pages, Victoria’s Secret has launched their presence on the runway and taken the world by storm, even generating a devoted fan base. Putting the fashion show on broadcast programming has allowed Victoria’s Secret to pervade a larger audience, authorizing Angels to strut their stuff right into the living rooms of millions. In front of millions eyes of all ages, Victoria Secret “creat[es] the illusion of this amazing body on the runway…but there are about 20 layers of makeup on my butt alone,” acknowledges one Angel, Selita Ebanks to the New York Daily News. Little does Victoria’s Secret attempt to separate fact from fiction for its viewers. Organizations such as the American Family Association and American Decency Association flood the Federal  Communications Commission (FCC) annually with complaints about the fashion show and Victoria’s Secret aired advertisements, claiming the sexualized airings as being indecent and obscene (FCC). The FCC ruled in 2001 that CBS’s broadcast of scantily clad Victoria’s Secret models was inoffensive, with FCC Commissioner Michael Copps stating, “when enforcing the indecency laws of the United States, it is the Commission’s responsibility to investigate complaints that the law has been violated, not the citizen’s responsibility to prove the violations…broadcasters would go the extra mile in exercising self-discipline when airing programming,” (FCC).

Communications Commission (FCC) annually with complaints about the fashion show and Victoria’s Secret aired advertisements, claiming the sexualized airings as being indecent and obscene (FCC). The FCC ruled in 2001 that CBS’s broadcast of scantily clad Victoria’s Secret models was inoffensive, with FCC Commissioner Michael Copps stating, “when enforcing the indecency laws of the United States, it is the Commission’s responsibility to investigate complaints that the law has been violated, not the citizen’s responsibility to prove the violations…broadcasters would go the extra mile in exercising self-discipline when airing programming,” (FCC).

As the fashion show keeps on getting bigger and more ostentatious, the fashion show is becoming less about the lingerie and more about the Angels sporting it. Although the show is made to showcase lingerie collections and sell product, most “outfits” exhibited on the runway are extremely over the top and are not even available for sale on store shelves. The tiny, sparkling lingerie sets, enormous feathered angel wings and teetering heels were in no shortage during last December’s Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show. Not to mention it brought together balloons, lace, fake fur, thigh high boots, a $10 million diamond encrusted bra and Taylor Swift. Millions tune in to watch every year, leaving women questioning how attainable “perfection” is. Whether it be healthy for our self-esteem or not, “women enjoy watching other women because they natural compare themselves to one another,” (Martin, 1997). But can society deem Victoria’s Secret as moral in having marketing model that can easily prompt wrecking havoc on female self-esteem?

Her Secret, from the Deontological Ethics perspective

In regards to sexual advertisements, deontological ethics “[address] the morality of using sexual appeals apart from their effects…how different sociocultural groups and values segments of people view such appeals, as well as how they come to do so,” (Gould, 1994).

Victoria’s Secret’s marketing model relies on sexual appeal, with advertisements featuring models oozing sensuality as they peer from their catalog pages, computer screens and TVs with seductive side-eyed stares. As a company always attracting attention for their sexual advertising, Victoria’s Secret often finds themselves a topic in the ethical dispute. Deontologically speaking, actual settlements pertaining the issue of Victoria’s Secret sexual  advertising appeals appear to “evolve in terms of what finally emerges in ads and what is restricted from ads,” (Gould, 1994). How did the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show evolve from a way to show off lingerie for the upcoming holiday in 1995, with “no fancy lighting and models just wearing underwear,” to an over-the-top fantasy extravaganza starring Angels sporting more feathers, diamonds and glitter than lingerie? (Lepore, Business Insider).

advertising appeals appear to “evolve in terms of what finally emerges in ads and what is restricted from ads,” (Gould, 1994). How did the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show evolve from a way to show off lingerie for the upcoming holiday in 1995, with “no fancy lighting and models just wearing underwear,” to an over-the-top fantasy extravaganza starring Angels sporting more feathers, diamonds and glitter than lingerie? (Lepore, Business Insider).

Victoria’s Secret is aware of how far they’re able to push the limits and where they need to stop. They know how much skin and sex appeal approaches the edge of censorship. Their advertisements approach that edge until it’s no longer the furthest limit, but normative. Then that aforementioned edge becomes redefined with sexier models and racier ads. For example, while American Family Association and American Decency Association have flooded the FCC with complaints about airing Victoria’s Secret’s over sexualized advertisements and fashion show, the CBS network ultimately acts as the policy maker in determining what advertising they will or will not accept. These tensions are “constantly being tested by advertisers who believe that sexual appeals enhance the effectiveness of their ads,” (Gould, 1994).

Victoria’s Secret isn’t selling bras and underwear; they’re defining sex appeal and selling body image. It’s undeniable Victoria’s Secret unabashed advertisements allure females into believing owning Victoria’s Secret lingerie will infuse the confidence and sexiness that the women in the advertisements ooze from every airbrushed pore. Their advertisements sway their female viewers into looking at their sex-kitten models and thinking, “why can’t I look like that?” But you don’t have to go too far, for a $64.99 lacy cream-filled push-up bra you can be a sex goddess too. From the deontological perspective, Victoria’s Secret use of sexual appeals exploit and degrade customers by using their “base instincts to cause consumers to buy ‘unneeded products,’” fostering an unhealthy relationship with materialism (Gould, 1994). Associating sexual prowess with lingerie in Victoria’s Secrets ads suggest promises of a plethora of self-confidence and love for your body with the purchase of every lacy thong.

The deontological ethics perspective isn’t finished pinning Victoria’s Secret as the bad girl quite yet, we still have to assess Victoria’s advertising ideology. Are using advertisements featuring models with long legs, thin waists and surprisingly large breasts merely a “marketing tool, interchangeable with other appeals such as humor and fear, or are these models used to promote a deeper agenda”, such as the idea of casual sex? (Gould, 1994). Making an assumption the Pink line asserts casual sex to its customer isn’t too far off, with the Bright Young Things Spring Break collection sporting underwear reading “Call Me”, “Wild”, and “Feeling Lucky?” Assertions of casual sex may be an involuntary consequence of being in the lingerie business, but  the Pink line is specifically targeted to the young teen demographic and made this consequence intentional. There’s no better way to sexualize the youth than to name a collection “Spring Break”, a term synonymous with carelessness and casual hookups. Spring break is

the Pink line is specifically targeted to the young teen demographic and made this consequence intentional. There’s no better way to sexualize the youth than to name a collection “Spring Break”, a term synonymous with carelessness and casual hookups. Spring break is

esoteric to young college kids, especially to the 15 and 16 year old girls who want to seem older. These girls are exactly who Chief Financial Officer Stuart Burgdoerfer admitted the line was targeted to. Are playful undies reading “Feeling Lucky?” too far? With line named “Spring Break”, featuring advertisements with messy-haired, carefree models looking to have some fun, it’s not a stretch to believe Victoria’s Secret may have a quasi-moralized agenda of promoting casual sex.

Can she define sex appeal?

Perhaps in focusing on the deontological ethics perspective and pinning Victoria’s Secret as the bad girl, we forgot to study the effects sexual advertising has on the consumer. Possibly another type of ethics, teleological ethics, would be a better perspective to analyze Victoria’s Secrets advertisements. In regards to sexual advertisements, teleological ethics “[address] the effects, harms, benefits and consequences of sexual appeals for all parties encountering them,” (Gould, 1994). Maybe Angels, the self-confident, golden goddesses sporting sex appeal you can finally own have taught women to learn to love their bodies. Teleologically speaking, some possible consequences the sexuality Victoria’s Secret’s ads make available to women could be women and sexual empowerment, or making sexuality a more acceptable and normative experience for teens as they transition into women.

There is no doubt the use of sexual advertising is the means that has allowed Victoria’s Secret to vitalized the lingerie industry and make lingerie mainstream. The company raked in $10.8 billion in sales in 2013, double what it was in 1982 when The Limited acquired Victoria’s Secret. But at what cost? (Finance N Investments). Deontological ethics tell us it’s Victoria’s Secret’s fault for using sexual appeal in their advertising and not considering their effects on society. There’s no denying an intended consequence of Victoria’s Secret is demoralizing women and misleading them to think buying their lingerie will fix their insecurities. The company has taken a sacred concept, the angel, and sexualized it to further advance the association of their lingerie with the predetermined body image their advertisements diffuse throughout society. Victoria’s Secret ads feature bombshell Angels begging you to buy their lifestyle and body, harassing and pleading their case every time your eyes run into them. They force you to further the unnecessary materialism with their promises of manifested sex appeal. We all know angels can do no wrong, right?

Works Cited

Adler, C. (2010, June 9). How Victoria’s Secret Made Lingerie Mainstream. Newsweek. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/how-victorias-secret-made-lingerie-mainstream-73325

Barbaro, Michael (2006, July 15). What Women Want; Underwear That Fits So Well It Can Be Outerwear. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D05E4DC1F30F936A25754C0A9609C8B63

Cherry, D. Victoria’s Secret: Pull ‘Bright Young Things’ Campaign. Change.org. Retrieved from https://www.change.org/p/victoria-s-secret-pull-bright-young-things-campaign?lang=tl

Federal Communications Commission, Statement of Commissioner Michael J. Copps On Complaints Received Regarding Broadcast of Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show (2001). Retrieved from http://transition.fcc.gov/Speeches/Copps/Statements/2001/stmjc128.html

Gould, S. J. (1994). Sexuality and ethics in advertising: A research agenda and policy guideline perspective. Journal of Advertising, 23(3), 73.

Groves, M. (1985, November 25). Frederick’s Tries to Update Its Image as Rivals Get Tougher. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1985-11-05/business/fi-4449_1_frederick-mellinger

Lepore, M., (2011, January 24). Everything You Need to Know About the Red-Hot, Growing Lingerie Industry. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-rapidly-growing-lingerie-industry-2011-1

Martin, M., (1997). Stuck in the Model Trap: The Effects of Beautiful Models in Ads on Female Pre-Adolescents and Adolescents. Journal of Advertising, 23 (2).

Merrick, A (February 29, 2008). Apparently, You Can Be Too Sexy. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB120421181615799917?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB120421181615799917.html

Newsom, G. (2013, April 5). The Problems with Victora’s Secret’s Marketing. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jennifer-siebel-newsom/the-danger-in-victorias-secrets-marketing_b_3024702.html

Pimentel, B. (1993, September 1). Lingerie Firm Founder Dies – Body in Bay Former Victoria’s Secret owner left car at bridge. San Francisco Chronicle.

Schiro, Anne-Marie (1982, May 15). Luxury Lingerie: A Mail-Order Success. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1982/05/15/style/luxury-lingerie-a-mail-order-success.html.

Victoria’s Secret Annual Report 2013. Finance N Investments (2013, December 19). Retrieved from http://www.financeninvestments.com/annual-report/victorias-secret-annual-report-2013.html.

Wattenburg, D. (2013, March 28). Online backlash grows against Victoria’s Secret’s racy Bright Young Things collection for teens. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/mar/28/online-backlash-grows-against-victorias-secret-rac/

Picture Sources

http://www.merkactiva.com/blog/el-secreto-de-victoria-es-el-marketing-integral/

http://www.playbuzz.com/stephanies15/can-you-name-these-victorias-secret-angels

http://www.trendnista.com/fashion-women/victorias-secret-pinks-look-book/

The teleology you mention here seems akin to consequenitialism.

LikeLike

There are several rich issues here that are worth remembering and perhaps further exploring. One is the shift in marketing from male purchasers to female. Does that mean the locus of change towards less-sexualized or unrealistic body image should be on women and nto men? Or both?

LikeLike

Also, do you think the fashion show is distinct from the core business model? From the catalog?

If VS says, “hey,we just sell what customers want,” what would you say?

LikeLike

This should not ever b aired on tv esp family shows. Its as bad as the hardee commercialsm I think u should be sued by all women who found it to be demeaning to women. Keep this on paid playboy channels

LikeLike

Honestly, you have good points and statistics to back up some of it my problem with this is that Victoria Secret Pink is NOT geared toward a young audience. It is geared toward college age women. If you do your research you will find that, that does not mean that younger girls will not shop there or want to shop there. With saying that it is not the brands fault, this is strictly parenting faults. If you do not want your child to be around something you are uncomfortable with you are responsible for that.

Another point is that the Victoria Secret models have great bodies that is no question, but it is literally their job to look good. They are advertising lingerie, it’s pretty obvious that is a sexual subject. Also it is a natural response to think “wow I wish I looked like that” that happens to anyone. If you’re an athlete and you look at David Beckham you’re automatically going to wish you looked like him. But if you let watching the fashion show or a commercial make you feel THAT bad about yourself that is personal insecurities that you should personally deal with because it’s the models job to look that perfect. If you are getting paid the amount of money they get paid to look good they’re clearly going to look good, do you see my point?

LikeLike

Thanks for comment. Just so you know, this was a student blog as part of a class last year. I am not sure the author will follow up.

LikeLike